Bad Blood? Appetite for State aid concepts in Southeast Asia since Taylor Swift’s exclusivity deal

Share

Earlier this year, Singapore subsidised Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour performance, in return for exclusivity in the region. The reaction by its neighbours demonstrates some appetite for Southeast Asia to adopt the principles that underpin State aid control in Europe. In this article, Urs Haegler and Jun Kai Wee [1] look at European Union State aid rules and the economic concepts that underpin them, and show how those principles could take root in Southeast Asia, allowing its own regime to develop incrementally.

View the PDF version of this article.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

Introduction

Over the Summer, Taylor Swift visited 17 European cities, in 11 countries, for 48 performances of her Eras Tour. Amid the excitement, the frenzy with which politicians – not just fans – had called for shows to be held in their cities seems a long time ago.

Back in 2023 world leaders such as Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Chilean President Gabriel Boric took to social media to make their pleas.[2] The reason was that The Eras Tour offered substantial reward for host cities. The “Swiftonomics” involved are well documented: Bloomberg estimated that the first leg of her US tour contributed $4.3 billion to the country’s GDP in 2023, and Barclays estimated that the Eras Tour would provide a £1 billion boost to the UK’s economy.[3]

A glance at Swift’s schedule shows that she played six nights in the Southeast Asia region; all of them in Singapore. It was, therefore, unsurprising news when, in February 2024, Thailand prime minister Srettha Thavisin revealed that Singapore government agencies had subsidised Taylor Swift’s concerts in the country. Part of the deal granted exclusivity to Singapore in the Southeast Asia region.[4]

The subsidy is controversial. Srettha expressed regret at not coming to similar arrangements; as did Indonesia Coordinating Maritime Affairs and Investment Minister Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan. However, others reacted more negatively; Philippines House Representative Joey Salceda, for instance, criticised the deal for being contrary to Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) relations and “what good neighbours do”.[5]

In this article, we look at European Union (EU) State aid rules and common economic concepts that underpin them. The reaction in Southeast Asia to the Eras exclusivity deal shows some appetite for similar principles to be applied in Southeast Asia. Although regional differences in context and regard to national sovereignty make it unlikely the region would adopt an analogous State aid regime in full, we show how the underlying economic principles could take root, allowing its own regime to develop incrementally.

What good neighbours do

A similar controversy could not conceivably have occurred in the EU, because a deal similar to the one that Singapore managed to strike (based on what is publicly known about it) would likely fall afoul of the bloc’s stringent State aid rules.

State aid control in the EU

Article 107 of the Treaty on Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) prohibits any aid granted by a Member State or through State resources in any form whatsoever which distorts or threatens to distort competition by favouring certain undertakings or the production of certain goods, in so far as it affects trade between Member States.[6] In other words, government interventions that fulfil the following criteria are prohibited:

- there has been government help or resources used. This can take a variety of forms (e.g. grants, interest and tax reliefs, guarantees, government holdings of all or part of a company, or providing goods and services on preferential terms, etc.);

- the intervention gives the recipient an advantage on a selective basis, for example to specific companies or industry sectors, or to companies located in specific regions;

- the intervention distorts or may distort market competition; and

- the intervention is likely to affect trade between Member States.[7]

Furthermore, the intervention must not fall under block exemptions, de minimis rules and aid schemes provided for in Article 107.[8]

It is likely the EU’s state aid rules would prohibit a European country seeking an agreement that reflects what is known about Singapore’s Eras Tour deal. In particular, Singapore confirmed government resources were used in the form of a grant, reported to be around US$2 million to US$3 million in total for all six shows.[9] The grant was specific to the Eras Tour in Singapore, and the requirement for exclusivity likely distorted competition with alternative venues in the Southeast Asia region as concertgoers would have had to travel to Singapore instead of elsewhere, affecting trade between countries in the bloc.

In practice, European Court case law establishes a very low threshold for the establishment of a distortion of competition and effect on trade under Article 107. There is no requirement to show that State aid will lead to consumer harm – which is what it is normally intended by ‘distortions of competition’ in other areas of competition law – and there is not even any need for extensive analysis showing a material distortion to the level playing field.

Reasons to control State aid

There are several reasons for controlling State aid.

Firstly, and most immediately, State aid can distort the competitive process and create an uneven playing field for businesses affected. In particular, foreign competitors expect that the recipient of investment aid will expand its capacity, and thus they will expect the residual demand that they compete for to reduce. In turn, that expectation may induce them to scale down their own investments. The overall effect shifts oligopoly rents towards the aid recipient, at the expense of its rivals and, ultimately, consumers.

Secondly, aid recipients may use the funds to pursue predatory pricing or acquisition strategies, leading to less competitive market structures.[10] Absent specific rules imposed by supranational blocs such as the EU and/or trade agreements, national governments have little incentive to establish a level playing field across national markets.

Thirdly, State aid weakens the extent to which the competitive process disciplines businesses. Economic history has shown that government handouts can breed complacency, inefficiency and perverse incentives in the businesses that receive such help. National markets will be negatively affected by these inefficient businesses.

Controlling State aid can facilitate coordination among national governments, providing a commitment mechanism that helps them to avoid “subsidy races”. Taking lessons from the Eras Tour, Thai and Indonesian leaders have already signalled their readiness to pursue similar deals to secure large performances in the future. In principle, the scale of the subsidy that each government is prepared to pay is capped by the incremental benefits that subsidy secures – for example, additional tax revenue or the economic benefit of tourists spending more. But a bidding war between governments would improve promoters’ bargaining position, enabling them to extract a larger proportion of the additional benefits for themselves. The same applies to other forms of state aid such as tax reliefs. Most prominently, in 2016 the EC found that Ireland granted Apple unlawful aid by artificially lowering taxes paid by Apple in Ireland since 1991. The European Court of Justice confirmed this decision in September 2024.[11]

ASEAN and resistance to State aid controls in Southeast Asia

There are other reasons for controlling state aid we do not cover here. These concern supranational objectives and national sovereignty that would be premature to discuss in the context of Southeast Asia. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is the regional community for Southeast Asia, and state aid control would straddle the fault line between its purposes and principles.

In particular, one of the purposes of ASEAN is to “create a single market and production base which is stable, prosperous, highly competitive and economically integrated with effective facilitation for trade and investment in which there is free flow of goods, services and investment; facilitated movement of business persons, professionals, talents and labour; and freer flow of capital”.[12] These objectives appear similar in spirit to the EU single market. So, given that State aid control is considered to support those objectives, the question arises why the ASEAN countries have not adopted similar rules.

In part, the reason reflects two of its fundamental principles: “respect for the independence, sovereignty, equality, territorial integrity and national identity of all ASEAN Member States” and “non-interference in the internal affairs of ASEAN Member States.”[13] Supranational mechanisms and institutions like state aid control are restrictions on national policymaking. The same is true for other mechanisms and institutions that the EU has – such as a single currency, regional central bank, and market regulators – that ASEAN has not (yet) embraced. The extent to which ASEAN Member States might, in the future, be willing to accept such restrictions in pursuit of a single market is a much broader question that is beyond the scope of this article.

Nevertheless, the development of State aid control in the EU provides a roadmap for how to navigate the tension between national sovereignty and economic integration/efficiency objectives.

Ultimately, State aid rules regulate the conduct of governments rather than companies. The two main actors, governments and the Commission, are political bodies and thus the interactions between them are often more political than technical. Furthermore, affected individuals and businesses have limited procedural rights in State aid control proceedings, leading to complaints that State aid procedures lack transparency and predictability.

Two characteristics of EU State aid control reflect these realities. Firstly, although in principle the EC has general discretion over the type of aid that is deemed compatible, the EC has adopted numerous guidelines on State aid design and control to provide greater transparency and limit the scope of its discretion to better resist political pressure over enforcement actions. Secondly, economic principles and tools have been introduced and strengthened successively, beginning with the EC’s 2005 State Aid Action Plan [14] which sought to increase transparency through, among other things, a refined economic approach.

State aid control in the EU has continued to evolve in the face of new learnings and challenges. For example, partly in response to the 2008 financial crisis, the EU began an effort to modernise state aid control in 2012 that among other things sought to streamline guidelines, rules and decisions.[15] More recently in 2020, the EU set out a temporary framework for state aid measures to support the economy in the current COVID-19 outbreak, [16] which would allow rapid approval for aid that meet certain criteria.

Disappointed Taylor Swift fans who missed the show may disagree, but the Singapore’s Eras Tour exclusivity deal was not a crisis by any measure. Still, it was a reminder that state aid control is a potential policy gap under the ASEAN framework, and that the conditions under which state aid control was deemed unsuitable for ASEAN should be re-examined in the light of new developments, such as in Southeast Asia market dynamics and public aspirations for further integration.

Examples of economic concepts and analysis that underpin state aid control in Europe

The implementation of state aid rules in the EU seems like a complex web of guidelines/notices, frameworks and case precedents in turn differentiated by sector and aid type.

Nonetheless, their apparent complexity is underpinned by a shared set of economic concepts. In practice, EU state aid control most often sees the use of economics in three areas, two concern criteria for State aid intervention and one concerns the regulation of a particular type of State aid:

- Economic advantage: Establishing whether the intervention gives the recipient an economic advantage – one of the conditions for identifying whether the intervention constitutes state aid and thus should be controlled.

- Compatibility: Determining whether a state aid’s positive effects in terms of a contribution to the achievement of well-defined objectives of common interest outweigh its negative effects on trade and competition in the common market.

- Public service compensation: Calculating the appropriate level of compensation for the provision of a service of general economic interest.

As discussed, the introduction and strengthening of economic principles and tools contribute to greater transparency and predictability, which in turn help to resolve the tension between national sovereignty and economic integration/efficiency objectives. A closer examination and understanding of how some common examples are applied would indicate how similar rules might develop in Southeast Asia. In particular, as we explore these examples in turn below, it will become apparent that while economic concepts are shared, these can be applied in State aid control via different ways across sectors – alternatively, they can be applied the same way for certain carve-outs.

Economic advantage

To determine if a particular government intervention satisfies the criterion, among others, that it gives the recipient an advantage and thus should be prohibited, EU courts have developed and applied variations of the Market Economy Operator (MEO) test. The MEO test assesses whether the relevant public body acted as a market economy operator would have done in a similar situation. If this is not the case, the beneficiary undertaking has received an economic advantage which it would not have obtained under normal market conditions, placing it in a more favourable position compared to that of its competitors.[17]

For example, the ‘market economy investor principle’ variant of the MEO test identifies the presence of State aid in cases of public investment (in particular, capital injections): to determine whether a public body's investment constitutes State aid, it assesses whether, in similar circumstances, a private investor of a comparable size operating in normal conditions of a market economy, such as a commercial bank, could have been prompted to make the investment in question. Similarly, the ‘private vendor test’ variant of the MEO test assesses, for a sale carried out by a public body, whether a private vendor under normal market conditions could have obtained the same or a better price.[18]

Typically, the MEO test requires a direct comparison of the state aid against similar private transactions under similar circumstances or an indirect comparison of the returns on the state aid against the market rate of return on assets with similar risk profiles.

Compatibility

Under Article 107.3, state aid generally prohibited under Article 107.1 may still be considered compatible with the EU common market if it contributes to well-defined objectives of common European interest. This compatibility assessment, like the MEO test, varies between different aid categories (e.g. aid in the field of R&D&I, Risk Capital, Environmental aid), but the variations share a common core approach in the form of a balancing test.[19]

The balancing test weighs the aid’s negative effects on trade and competition in the common market against its positive effects in the common interest via the following questions:

- Is the aid measure aimed at a well-defined objective of common interest?

- Is the aid well designed to deliver the objective of common interest i.e. does the proposed aid address the market failure or other objectives?

- Is the aid an appropriate policy instrument to address the policy objective concerned?

- Is there an incentive effect, i.e. does the aid change the behaviour of the aid recipient?

- Is the aid measure proportionate to the problem tackled, i.e. could the same change in behaviour not be obtained with less aid?

- Are the distortions of competition and effect on trade limited, so that the overall balance is positive?[20]

Economic analysis can be used to answer these questions. Firstly, it can help to demonstrate the existence of efficiency market failures, in the form of oversupply, undersupply or excessive costs. They can also help to demonstrate the existence of equity market failures in the form of social or regional disparities through statistical indicators such as GDP per capita, unemployment levels, participation rates in the labour market, poverty indicators, etc.[21]

Secondly, economic analysis can help in the design of aid schemes, typically through the identification and analysis of benchmarks or counterfactuals. For example, such analysis can be used to demonstrate the incentive effect, where the aid recipient would not undertake the targeted activity without aid, as well as proportionality, where less interventionist designs do not achieve the desired effect.[22]

Finally, economic analysis can help to determine the extent, if any, of the aid’s impact on competition and trade. In particular, economic analysis can help with market definition to identify the products and regions affected, as well as extent of differentiation and impact.[23]

Public service compensation

The EU identifies Services of General Economic Interest (SGEI) to be commercial services of general economic utility subject to public-service obligations, such as transport, energy, communications and postal services.[24] The EU controls state aid in the context of SGEIs through a specialised package of guidelines, exemptions, case-law and specific framework.[25]

Past the various thresholds and criteria, economic analysis plays a significant role when calculating the appropriate amount of compensation to provide the SGEI. In particular, the amount of compensation must not exceed what is necessary to cover the net cost of discharging the public service obligations, including a reasonable profit. In other words, net cost and reasonable profit levels have to determined.[26]

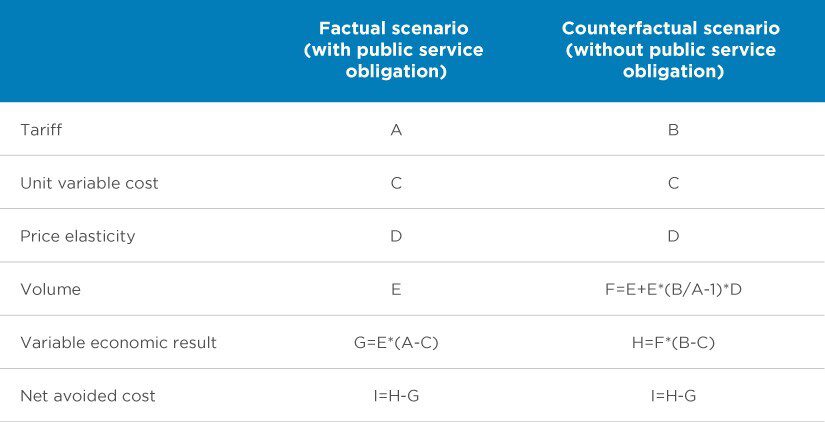

When it can be used, the net avoided cost methodology is considered the most accurate method for determining the cost of a public service obligation. Under the net avoided cost methodology, the net cost necessary, or expected to be necessary, to discharge the public service obligations is calculated as the difference between the net cost for the provider of operating with the public service obligation and the net cost or profit for the same provider of operating without that obligation, including intangible benefits. Similarly, a reasonable profit is the rate of return on capital that would be required by a typical company considering whether or not to provide the SGEI for the relevant duration, taking into account the level of risk.[27]

For example, Table 1 below broadly illustrates the EC’s approach to calculating the net avoided cost of Poste Italiane S.P.A.’s (PI) obligation to offer reduced tariffs to publishers and not-for-profit organisations, when Italian authorities notified the EC of the compensation for this service in 2019.[28] In particular, the EC considered that (i) in the counterfactual PI would have set tariffs to publishers and not-for-profit organisations at the higher, capped Universal Service Obligation (USO) price; and (ii) it was possible to estimate the price elasticity of demand based on a 5-month period in 2010 when PI applied the USO price to its press distribution mission. Based on these, the EC compared variable profits in the factual and counterfactual scenarios to calculate net avoided cost.

Table 1: Net avoided cost calculation

State aid control for ASEAN

The reaction to the Eras deal shows that, notwithstanding national sovereignty concerns, there may be some appetite in Southeast Asia for State aid principles to be adopted in some form.

To do that, ASEAN need not adopt the seemingly complex set of EU state aid controls in full. The economic concepts that underpin state aid in Europe indicate how similar measures might take tentative root in Southeast Asia. In particular, the MEO test and compatibility assessment have different applications for different sectors under EU state aid rules. In addition, SGEIs comprise a regulatory carve-out with different treatment and analysis. Similarly, for Southeast Asia limited state aid controls may be implemented in a few limited sectors first, with maximum flexibility for Member States to interpret and legislate rules locally.

These may then be gradually broadened and standardised. In fact, ASEAN is no stranger to such a step-wise, flexible approach and can look internally to regional competition policy for a good example of how this might work. In 2010, ASEAN set a goal for the introduction of competition policy in all member states by 2015 with no prescriptions on how this might look like in each country.[29] As a result, competition policy in Southeast Asia has developed at a pace and in unique ways suited to each jurisdiction. For example, aside from varying arrangements between national competition authorities and sectoral authorities, in Singapore vertical agreements remain exempt from competition law against anti-competitive agreements, although they may be caught as an abuse of dominance. Similarly, whilst Malaysia has not to date adopted merger control outside of specific sectors, policy changes are under way, demonstrating that an incremental approach to introducing regulatory controls may be the way forward.[30] More broadly, competition policy in Southeast Asia is enforced by national authorities, and the relatively new UK subsidy control regime may provide a viable model for regional State aid control with a similar absence of supranational enforcement.[31]

There are good reasons for state aid control in ASEAN and experience in the EU and ASEAN both show a practical way forward for implementation should stakeholders wish it. If so, perhaps one day ASEAN state aid rules will even be mandatory reading for Taylor Swift undergraduate courses.[32]

View the PDF version of this article.

References

-

Urs Haegler is a Senior Vice President at Compass Lexecon. Jun Kai Wee is a Senior Economist at Compass Lexecon. The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

-

Forbes, 8 July 2023, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

Bloomberg, 5 June 2024, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

The Guardian, 19 February 2024. See here, accessed July 2024.

-

Jakarta Post, 8 March 2024, see here and The Diplomat, 29 February 2024, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

Article 107(1), TFEU.

-

Article 107(2), TFEU.

-

European Commission, state aid overview, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

Channel News Asia, 1 March 2024, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

On the specific conditions required for competitive distortions via these mechanisms and mitigating factors, see, e.g., David Spector (2009), State Aids: Economic Analysis and Practice in the European Union.

-

M. Vestager, European Commission, see here, accessed September 2024.

-

ASEAN Charter, Chapter I, Article 1.

-

ASEAN Charter, Chapter I, Article 2.

-

European Commission, State Aid Action Plan, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

European Commission 2016/C 262/01, ¶ 75, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

European Commission 2016/C 262/01, ¶ 75, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

European Commission 2016/C 262/01, ¶ 75, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

European Commission 2016/C 262/01, ¶ 74.

-

European Commission (2009). Common Principles For An Economic Assessment Of The Compatibility Of State Aid Under Article 87.3, p 4-5, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

European Commission (2009). Common Principles For An Economic Assessment Of The Compatibility Of State Aid Under Article 87.3, ¶ 9.

-

European Commission (2009). Common Principles For An Economic Assessment Of The Compatibility Of State Aid Under Article 87.3, ¶¶ 19 and 29.

-

European Commission (2009). Common Principles For An Economic Assessment Of The Compatibility Of State Aid Under Article 87.3, ¶¶ 31, 35 and 40.

-

European Commission (2009). Common Principles For An Economic Assessment Of The Compatibility Of State Aid Under Article 87.3, ¶¶ 53-55.

-

European Union, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

European Union, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

European Commission 2012/C 8/03, ¶ 21, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

European Commission 2012/C 8/03, ¶¶ 24-38.

-

European Commission SA.48492, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint 2010.

-

The Star, 4 January 2024, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

UK subsidy control regime, see here, accessed July 2024.

-

For example, Harvard University, see here, accessed July 2024.