Dynamic markets and stale market definitions: The snowballing burden of legacy market segmentations in media mergers

Share

Market definition can be a balancing act between a forward-looking approach and drawing on precedent from previous cases. In light of this, regulators may seek to leave market definitions open, arguing that closing them is a waste of resources when it does not impact the assessment. In this article, Lau Nilausen [1] argues that the balancing act may have swung towards superficial regulator prudence. He looks at markets in media mergers and argues that the practice of leaving market definitions open has created a snowballing regulatory burden that is unnecessary for the merging parties, ultimately hindering the efficiency of merger assessments.

View the PDF version of this article.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

Introduction

Mergers can be the most direct way to shake up markets or create something entirely new.[2] Whilst competition regulators need to ensure that mergers do not materially undermine competition, [3] unnecessary practical hurdles to mergers may stymie transactions “capable of increasing the competitiveness of European industry, improving the conditions of growth and raising the standard of living in the Community”.[4]

Merger assessments are supposed to be forward-looking to “determine the likelihood of certain developments in the relevant market within a foreseeable time frame”, including “how such a concentration might alter the parameters of competition”.[5] Even so, it is only natural that regulators tasked with assessing the potential impact of mergers look to past cases for clues about how markets may work and potential sources of concern. This may enhance the efficiency of the regulatory review process. However, where regulators draw on such experience, they also must be mindful to not mechanistically assess the transaction at hand through the prism of past decisions.

The point above hopefully is uncontentious. But in practice it is a nuanced balancing act. Based on analyses of the European Commission’s (the “Commission”) assessments of mergers in media markets, [6] this article argues that the pendulum may have swung too far in the direction of superficial regulatory prudence by imposing on merging parties the need to prove absence of possible anti-competitive effects in markets that have never actually been confirmed to exist.

The opportunities and burdens of market definitions left open

Leaving a market definition open can (i) be a helpful way for merging parties to proactively demonstrate that a transaction does not raise concerns across potentially relevant market definitions, (ii) be a way for the regulator to address uncertainty around the likely post-transaction development of an industry, and (iii) promote efficiency by freeing up resources that otherwise would have been needed to finalise market definitions.[7] Open market definitions may therefore seem superficially appealing.

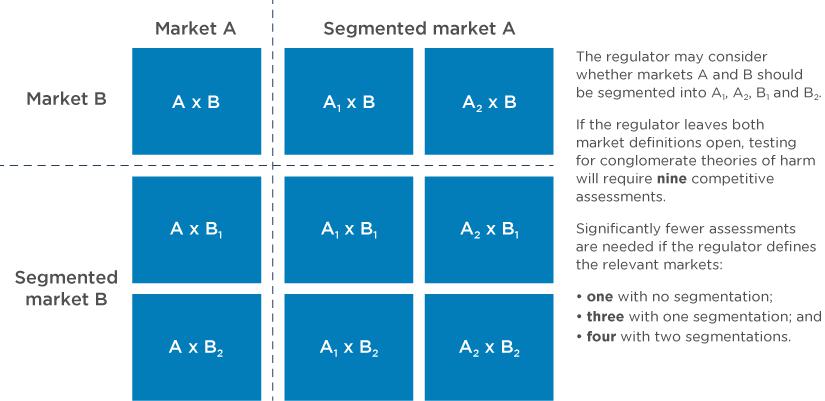

However, leaving market definitions open has a cost. Parties must derive market shares for hypothetical market segments they may not rationally track during their normal course of business. Additionally, those hypothetical market segmentations also exponentially increase the number of combinations of potential markets for which regulators need reassurance that there can be no conglomerate theories of harm. Figure 1 illustrates the snowballing impact this has. So, although leaving market definitions open may save resources related to work on market definition, it has a compounding opposite effect on the resources needed to assess potential effects on competition.

Figure 1: The number of possible competitive assessments in a conglomerate merger

In principle, the Commission is required to take a forward-looking approach to market definition when developing hypotheses for market definitions and segmentations.[8] In practice, the Commission requires the notifying party to submit “all plausible alternative product and geographic market definitions” explaining that “plausible alternative product and geographic market definitions can be identified on the basis of previous Commission decisions and judgments of the Union Courts”.[9] However, inconclusive market definitions are exactly that: inconclusive. Without a final decision on whether or not a particular market exists, there can be no presumption in future cases that such a market actually is (or ever was) plausible or has any commercially meaningful interpretation. Market definitions left open in previous decisions may thereby inappropriately increase the burden on subsequent merging parties.

To illustrate the issue, this article examines market definitions in media mergers specifically. It provides a brief introduction to market definition in media mergers and the current myriad of associated hypothetical segmentations. It then analyses in depth how the Commission has assessed, or not assessed, various segmentations for these services over time and the implications thereof in light of recent market development.

Media mergers: open market definitions create mounting regulatory obstacles

Media mergers can involve multiple stages of an evolving value chain going from production of content to consumption across different platforms. In short:

- Consumers access media content at home through (i) streaming services, (ii) publicly available broadcast services (so-called free-to-air, or FTA), or (iii) pay-TV services. The Commission terms this “Retail supply of AV services to end customers”.

- Pay-TV operators may aggregate multiple TV channels into packages. This involves pay-TV operators acquiring the right to carry those channels, or channels paying to be included on the pay-TV operators’ platforms. The Commission terms this “Wholesale supply of TV channels”.

- Suppliers of TV channels and operators of streaming services acquire content by either (i) licensing it from owners of existing content (so-called licensed content), or (ii) creating new content in in-house studios or by contracting with external suppliers for such productions (so-called “commissioned content”). These activities fall into what the Commission terms “Production and supply”.

The Commission has considered multiple market segmentations within or across the abovementioned levels of the value chain. These segmentations can be aggregated by:

- Business model, including segmenting between (i) FTA and pay-TV, (ii) linear and non-linear TV channels, and (iii) distribution technology;

- Premium/non-premium content, including a variety of markers of quality across pricing and the exhibition window of films;

- Genre, including segmentations into (i) scripted and non-scripted shows (e.g. reality TV versus drama), (ii) sports versus film versus other contents, (iii) US and non-US films and (iv) type of sport events; and

- Cost structure of production and supply, including segmentations between licensed content and commissioned content and in-house and external productions.

Of the resulting 21 potential market segments that the Commission has considered across the value chain in its decisions, 12 have either (i) been dismissed or left open, (ii) always been left open, or (iii) been left open but for in a single case. For another five, the Commission did make positive findings of a relevant market for more than one case but subsequently left the question open.

As documented throughout this article, merging parties as a result are called upon to analyse numerous hypothetical markets that (i) have not been confirmed to actually exist, (ii) for which no positive finding of existence has been made for sometimes more than a decade, or (iii) have been found to exist at some point but which subsequent market developments may have rendered obsolete. This raises real hurdles for merging parties seeking the timely completion of what may be uncomplicated mergers. Truly efficient merger assessments may therefore require regulators to actually define the relevant markets, or at the very least not impose obligations on merging parties to prove absence of problems in markets that in the past have been merely hypothesised.

Segmentation by business model

The Commission has considered business model as a dimension of segmentation in some form across all levels of the value chain. This includes (i) FTA/pay-TV, (ii) linear/non-linear distribution, and (iii) distribution technology, as set out in turn below.

FTA versus pay-TV

The Commission has assessed whether there are separate relevant markets for FTA and pay-TV across all levels of the value chain.

For retail supply of AV services to end customers, the Commission defined distinct markets for FTA and pay-TV services over the period between 1991 and 2010.[10] This was originally on the basis that “to justify the payment of the subscription fee, pay-TV channels broadcast specialised programmes catering for the needs of a precise target audience”.[11] The Commission has based such segmentation on several other arguments, including (i) FTA is advertisement funded whereas pay-TV is subscription funded, [12] (ii) willingness to pay shows that pay-TV users place great value on additional content, [13] (iii) FTA targets audience share whereas pay-TV targets user numbers, [14] (iv) differences in types of content and schedules, [15] (v) inability of FTA operators to offer pay-TV services and vice versa, [16] and (vi) differences in hardware requirements and functionality for consumers.[17]

From 2010 onwards, the Commission has left open the question of separate markets for FTA and pay-TV in the context of retail supply of AV services to end customers.[18]

For wholesale supply of TV channels, the Commission argued for separate FTA and pay-TV markets in 2003 on the basis that there is a clear distinction between FTA and pay-TV channels for customers and suppliers.[19] This was due to (i) limited demand substitutability due to differences in content and programming schedules, [20] (ii) differences in consumer preferences, [21] (iii) differences in hardware and functionality, [22] and (iv) low supply-side substitutability due to differences in revenue models.[23] The Commission relied on similar reasoning up until 2018.[24]

Over the same period, the Commission left the question open in a Dutch case in 2011 [25] and considered FTA and basic pay-TV channels to be part of the same market in 2015 in a Belgian case, observing that “the vast majority of households subscribe to a basic pay TV package”.[26]

In later cases, the Commission has left the question open, [27] explaining e.g. in Discovery/WarnerMedia that “the market investigation has confirmed that the segmentation is still relevant in a majority of Member States under investigation” but that “In other Member States, the views were mixed or inconclusive.”[28]

For production and supply, the Commission in 2003 found separate markets for FTA and pay-TV on the basis that “expensive contents cannot usually be viewed on free TV”.[29] The Commission also defined separate FTA and pay-TV markets in 2008 explaining that “the business model in the context of which the acquired content is used by broadcasters (e.g. different programming, specific target groups, offer packaging) plays an important role in distinguishing between pay-TV and FTA TV”.[30]

In summary, there is precedent for the Commission defining separate markets for FTA and pay-TV, though the Commission has left the issue open in recent cases and thereby has not come to a definitive view on whether such market segmentation remains relevant. A weakening case for such segmentation is consistent with the Commission’s explanation back in 1998 that “as digitalisation continues to spread, there could admittedly, with the passage of time, be a certain convergence between pay-TV and free TV”.[31] This is against a starting point in 1991 in which the Commission acknowledged that “the value of pay-TV to a consumer can only be determined in relation to the alternative viewing possibilities of free access channels” such that “even if pay-TV represents a separate product market, it remains dependant on the quality and specificity of TV programmes on free access channels”.[32]

Linear versus non-linear

Linear TV channels provide for scheduled programming whereby the content is only available at a specific time. Non-linear distribution allows consumers to choose when to watch the available content (e.g., VOD services).[33] Non-linear services offered to consumers in addition to linear broadcasting of channels are known as “ancillary services”. The Commission has assessed whether linear and non-linear services constitute separate markets at the retail supply of AV services to end customers and wholesale supply of TV channel levels of the value chain.

For retail supply of AV services to end customers, the Commission concluded in 2003 that various non-linear services “could be considered as segments within the pay TV market”,[34] and in 2010 that “non-linear services and linear channels belong to two separate markets”.[35] The Commission found in 2014 that “it is becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish between the two” [36] and has since left the issue open.[37]

For wholesale supply of TV channels, the Commission concluded in 2015 that ancillary services are licensed “along with, or in addition to, [linear] channels, and not on a distinct stand-alone basis separately from the channels to which they relate”.[38] The Commission concluded similarly subsequent cases in 2021 and 2022.[39]

With the exception of News Corp/BskyB in 2010 for retail supply of AV services to end customers, the Commission has not found sufficient grounds for segmenting markets between linear and non-linear AV services. Doing so going forward would seem increasingly difficult as more and more content becomes available on non-linear services.

Distribution technology

Providers of content may reach consumers e.g. through cable, satellite, terrestrial TV and IPTV. The Commission has assessed segmentation across distribution technology at the retail supply of AV services to end customers and wholesale supply of TV channel levels of the value chain.

For retail supply of AV services to end customers, the Commission has either (i) concluded against any segmentation by distribution technology, [40] or (ii) left the question open.[41]

For wholesale supply of TV channels, the Commission also has either (i) concluded against any segmentation by distribution technology, [42] or (ii) left the question open.[43]

The absence of any precedent positively finding support for such segmentation undermines continued hypotheses of such segmentation.

Segmentation by premium/non-premium content

The Commission has assessed whether there are separate relevant markets for premium and non-premium content across all levels of the value chain.

For retail supply of AV services to end customers, the Commission has consistently left open the question of a potential segmentation between basic and premium pay-TV services.[44]

For wholesale supply of TV channels, the Commission initially left the question open [45] but then found separate product markets for “basic pay TV channels and premium pay TV channels” over the period 2014 to 2018.[46] The segmentation was based on “differences in content offering, pricing conditions and size of the audience attracted between Basic and Premium Pay TV channels”.[47]

In 2021, the Commission noted “the absence of a consistent definition of which pay TV channels would qualify as basic and which as premium” and that “TV content are distributed to different channels that market themselves both as basic and premium TV channels”, [48] and left the market definition open.[49] The Commission left this segmentation open again in 2022.[50]

For production and supply, the Commission has consistently left open the question whether “a distinction should be drawn between premium and non-premium audiovisual content”.[51] However, the Commission has in several cases separately identified distinct markets based on the so-called exhibition window.[52] The reasoning for such segmentation includes (i) that “it is necessary for a pay-TV operator to acquire key quality inputs such as premium films”, [53] and (ii) “the level of prices and the structure of remuneration [for VOD broadcasting rights] which make it possible to identify this type of rights separately within the upstream market”.[54]

The Commission has left the issue of segmentation by exhibition window open in several decisions, including all decisions since 2014.[55] The Commission’s reasoning for this includes that “from the demand side, there does not appear to be any intrinsic difference between the type of non-film, non-sport content that a TV broadcaster, a TV retailer and/or an OTT platform would source or commission from a TV production company, depending on the exhibition window in which it intends to broadcast such content on Pay TV or on FTA TV”.[56]

Absent a sufficiently robust distinction between premium and non-premium content at retail level, it is not clear on what basis there would be such a distinction in the upstream markets in which suppliers of AV services to end customers source content. Moreover, the emergence of global streaming services offering a combination of large-budget productions and deep catalogues of other content to attract and retain customers may further strain differentiation based on “content offering, pricing conditions and size of the audience” or exhibition windows as new content is made immediately available at accessible prices.

Segmentation by genre

The Commission has considered genre as a dimension of segmentation at the wholesale supply of TV channels and production and supply levels of the value chain.

For wholesale supply of TV channels, the Commission has considered “whether separate markets should be identified based on the theme of the channel (e.g., films, sports, news etc.)”, [57] “general interest and thematic channels”, [58] and premium pay-TV film and sports channels.[59] In all instances, the Commission left the question open.[60]

For production and supply, the Commission has considered four different potential segmentations by genre: (i) scripted/non-scripted, (ii) sport/film/other, (iii) US/non-US films, and (iv) by type of sports event.

The Commission has left the question of segmentation between licensing of scripted and non-scripted content open.[61]

In relation to segmentation between sport, films, and other content, the Commission has generally left the question open.[62] The exceptions are (i) a finding of separate markets in 2000 for “feature films and made-for-TV programmes [as these] do not have the same value in terms of consumers’ attractiveness”, [63] and (ii) certain types of sports, as discussed further below.

In relation to segmentation between US and non-US films, the Commission has generally left the question open, [64] with the exception of Sogecable/Canalsatelite Digital/Via Digital in 2002.[65]

In relation to segmentation by type of sport events, the Commission has found that:

- “Football broadcasting rights may not be regarded as substitutes to other sports. This is due to football’s pre-eminence as the singularly most popular sport across most EEA Member States, regularly attracting wider audiences which are rarely matched by other sports”.[66] The Commission further identified separate markets for football broadcasting rights to events that are played “regularly throughout every year” and “more intermittently, every four years” [67] on the basis that “not all events have the faculty to generate the same revenue due to a different timing”.[68]

- Broadcasting rights to football events that are played regularly throughout every year involving foreign football clubs are not substitutes for rights to broadcast events involving local clubs.[69]

The Commission has left the question of whether rights to broadcast other types of sport may constitute separate markets.[70] In the Discovery/Polsat/JV decision in 2020 the Commission stated that “few respondents [to the market investigation] indicate[d] that a segmentation of sports content should be subdivided by sport discipline”, [71] and left the question open.[72]

In summary, the only examples of the Commission actually defining separate markets based on genre include a one-off instance of defining a market for licensing of feature films in 2000, a one-off instance of defining a market for US feature films in 2002, and several instances of identifying separate markets for certain football rights.

The emergence of the so-called Golden Age of Television based on high-budget, feature film quality TV series raises possible questions about whether licensing of feature films still realistically could represent a separate market for broadcasters. Moreover, the embrace by streaming services of such content sourced globally to successfully compete with traditional pay-TV offerings would seem to further undermine any notion that non-sport content of a particular origin and type could be so insulated from competition as to represent a separate relevant market.

In addition to the above, the emergence of streaming platforms may again challenge past reasoning for identifying separate markets for certain types of sports content. Several streaming platforms have grown to global scale based on non-sport content and only started bidding for, and sometimes winning, rights to broadcast high value sport content. This again challenges the notion that such content was must-have or otherwise critical for the ability of content providers to compete.

Segmentation by cost structure

The Commission has considered cost structure as a dimension of segmentation at production and supply level of the value chain.

The Commission has generally defined separate markets for licensing and commissioning.[73] This is based on findings that (i) “Acquiring pre-produced TV content tends to be cheaper because the rights owner is able to grant multiple licenses with a more limited scope for the same TV content”; [74] (ii) “certain types of TV content (e.g., live entertainment and locally originated TV content as opposed to international/US films and TV series) are typically not available in pre-produced format, but must either be commissioned or produced in-house by the broadcaster”, [75] (iii) “the need to offer a given range of TV content”, [76] and (iv) “many broadcasters have separate budgets for tailor-made TV content and pre-produced content”.[77]

Within commissioning, the Commission has considered whether there are separate markets for productions sourced in-house and externally. The Commission has generally excluded in-house productions from AV production markets.[78] The Commission’s reasons for doing so include that (i) broadcasters incurring largely fixed costs for in-house production capabilities are incentivised to make full use of their capacity rather than incurring costs with external suppliers, [79] (ii) broadcasters have in-house experience and know-how for certain types of programming (“information, culture, youth, documentaries, sports and some types of entertainment”) but not for other types (“large scale entertainment programmes”), [80] (iii) broadcasters do not have the rights to produce certain programming, [81] (iv) in-house productions are not made available to third parties within the relevant geographic market, [82] and (v) not all broadcasters have in-house capabilities.[83] In several cases, the Commission referred to precedent without explaining its exact reasoning.[84] In one case the Commission relied on similar reasoning but left the market definition open.[85]

The Commission’s Telefonica/Endemol decision included in-house production in a wider commissioning market on the basis that “programmes produced in-house by TV broadcasters are in some cases sold to third parties” and therefore was “in direct competition with programmes produced by independent producers”.[86] The Commission contrasted this to previous decisions in which “in-house production of TV broadcasters was excluded from the relevant product market because it was only intended for captive use in the relevant geographical markets”.[87]

Commissioning of content may not only enable a broadcaster to service its end customers but may also open up revenue streams from licensing to other broadcasters.[88] Commissioning can also be a way to secure exclusive territorial rights for content and thereby improve the competitiveness of a broadcaster. Any assessment of whether there is substitution between licensing content from third parties and commissioning will therefore need to consider not only the costs but the overall economics of these options.

The emergence of streaming services may increase the competitive friction between licensing and commissioning. Streaming services can have (i) greater scale, and (ii) a greater need for competitive differentiation than has traditionally been the case for national broadcasters. This improves the economics of commissioning compared to licensing content. Moreover, regulatory obligations on streaming services to carry locally produced content encourages these services to partner with local broadcasters to commission local content with a cross-border appeal. This improves the economics of commissioning content also for local broadcasters. Whereas the Commission has clear precedent for separate markets for commissioning and licensing of content, this may require more detailed assessment going forward depending on the facts of the case.

A forward-looking view

The Draghi Report argues that “Competition authorities need to be more forward-looking and agile”, noting that “since the articles in the Treaty are already worded broadly enough to allow the Commission to account for innovation and future competition in its decisions, what is needed is a change in operating practices”.[89]

The assessment of mergers should already be forward-looking by design. Yet the analysis above indicates that merging parties may need to overcome regulatory concerns anchored in market definitions that may merely have been hypothesised as potentially plausible in the past rather than established as relevant for the merging parties’ current and future operating environment based on an individual appraisal of the circumstances relevant to the transaction. For prospective merging parties and their advisors, this is a risk that needs to be considered. For regulators, this represents an opportunity to further streamline the merger assessment process by implementing a truly forward-looking view.

View the PDF version of this article.

References

-

Lau Nilausen is a Senior Vice President at Compass Lexecon. The author gratefully acknowledges the contribution of Joanna Hornik and Adrian Er. The author thanks Andy Parkinson, Rameet Sangha, and the Compass Lexecon EMEA Research Team for their comments. The views expressed in this article are the views of the author only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

-

P. Gaughan, Mergers, Acquisitions, and Corporate Restructurings (7th edition Wiley, 2017), page 127.

-

Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings (the EC Merger Regulation), recital 5.

-

EC Merger Regulation, recital 4.

-

Case C-376/20 P, Commission v CK Telecoms UK Investments EU:C:2023:561, paras. 82 and 84.

-

In practical terms, the underlying analysis takes as its stating point the Commission’s assessment of the Discovery/WarnerMedia transaction (one of the most recent transactions), works backwards to identify the origin and development of markets considered in that context, and assesses how these were considered in the largely contemporaneous Amazon/MGM transaction. This covers transactions going back more than 30 years. Whereas advertisement revenue is important to certain retail supply business models, this article does not explore the dynamics of this business.

-

Commission Staff Working Document, Evaluation of the Commission Notice on the definition of relevant market for the purposes of Community competition law of 9 December 1997 (SWD(2021) 199 final: “the Commission may leave market definitions open in cases where no competition concerns arise. This practice has the effect of limiting the burden on companies to supply information”.

-

Case T-334/19, Google AdSense for Search EU:T:2024:634, para. 238: “The Commission is required to carry out an individual appraisal of the circumstances of each case, without being bound by previous decisions concerning other undertakings, other product and service markets or other geographic markets at different times”.

-

Form CO, section 6.

-

M.110 ABC/General Des Eaux/Canal+/W.H. Smith, para. 9.a. See also M.993 Bertelsmann/Kirch/Premiere para. 18; M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiù, para. 47; M.5121 Newscorp/Premiere, para. 27; and M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, para. 99.

-

M.110 ABC/General Des Eaux/Canal+/W.H. Smith, para. 11.

-

M.993 Bertelsmann/Kirch/Premiere para. 18; M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiù, paras. 20 and 24; M.5121 Newscorp/Premiere, paras. 15 and 19; M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, para. 97; and M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 107.

-

M.993 Bertelsmann/Kirch/Premiere para. 18; M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiù, para. 33; M.5121 Newscorp/Premiere, paras. 15 and 18; M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, para. 97; and M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 107.

-

M.993 Bertelsmann/Kirch/Premiere para. 18; and M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiù, para. 21.

-

M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiù, para. 20. See also M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiù, paras. 21, 22, 24, 27, and 30; M.5121 Newscorp/Premiere, paras. 15 and 17; M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, para. 97; and M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 107.

-

M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiù, para. 20; Newscorp/Premiere, para. 19; and M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, para. 97.

-

M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiù, para. 36.

-

M.6369 HBO/Ziggo/HBO Nederland, paras. 30-31; M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 108; M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, para. 120; M.8665 Discovery/Scripps, paras. 31-32; M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 98; M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, para. 63; and M.10349 Amazon/MGM, para. 74.

-

M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiú, para. 47.

-

M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiú, paras. 20-22, 24-27, 29-31, and 38.

-

M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiú, para. 33.

-

M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiú, paras. 35-36.

-

M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiú, paras. 20 and 24.

-

M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, paras. 83 and 85; M.6369 HBO/Ziggo/HBO Nederland, paras. 24 and 27; M.8665 Discovery/Scripps, para. 23; and M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 85.

-

M.6369 HBO/Ziggo/HBO Nederland, paras. 24 and 27.

-

M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, paras. 86, 90 and 91.

-

M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, paras. 78 and 79; M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, para. 43; and M.10349 AMAZON/MGM, para. 54.

-

M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, para. 38.

-

M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiu, para. 54.

-

M.5121 News Corp/Premiere, para. 29.

-

M.993 Bertelsmann/Kirch/Premiere, para. 18.

-

M.110 ABC/General Des Eaux/Canal+/W.H. Smith, para 11.

-

M.10349 AMAZON/MGM, para. 52.

-

M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiù, para. 43.

-

M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, paras. 106 and 107.

-

M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 109.

-

M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, paras. 109 and 110. See also M.8354 Fox/Sky, para. 98; M.8665 Discovery/Scripps, paras. 31 and 32; M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 98; M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, para. 63; and M.10349 AMAZON/MGM, paras. 70 and 74.

-

M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, para. 93-94.

-

M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, para. 43; and M.10349 AMAZON/MGM, para. 54.

-

M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, para. 105; M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 113; and M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, paras. 62 and 63.

-

M.5121 News Corp/Premiere, para. 22; M.6369 HBO/Ziggo/HBO Nederland, para. 31; M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, para. 127; M.8665 Discovery/Scripps, para. 33; M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 98; and M.10349 AMAZON/MGM, para. 74.

-

M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, paras. 90 and 91; M.9064 Telia Company/ Bonnier Broadcasting Holding, para. 162; M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, para. 43; and M.10349 AMAZON/MGM, para. 54.

-

M.6369 HBO/Ziggo/HBO Nederland, para. 27; M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, para. 98; and M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 85.

-

M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, para. 119; M.8665 Discovery/Scripps, paras. 31-32; M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 137; M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, para. 63; and M.10349 AMAZON/MGM, paras. 69 and 74.

-

M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, para. 85; and M.6369 HBO/Ziggo/HBO Nederland, paras. 24 and 27.

-

M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 113; M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, para. 89; M.8665 Discovery/Scripps, para. 23; and M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 85.

-

M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 104; and M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, para. 82.

-

M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, para. 39.

-

M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, para. 43.

-

M.10349 AMAZON/MGM, paras. 50 and 54.

-

M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, paras. 62 and 66; M.6369 HBO/Ziggo/HBO Nederland, para. 21; M.8354 Fox/Sky, para. 68; M.8665 Discovery/Scripps, para. 20; M.10343 Discovery/Warner Media, para. 25; and M.10349 Amazon/MGM, para. 36.

-

M.2050 Vivendi/Canal+/Seagram, para. 21; M.4504 SFR/Télé 2 France, para. 29; and M.6369 HBO/Ziggo/HBO Nederland, para. 20.

-

M.2050 Vivendi/Canal+/Seagram, para. 21.

-

M.4504 SFR/Télé 2 France, para. 29.

-

M.2845 Sogecable/Canalsatelite Digital/Via Digital, para. 25; M.5121 News Corp/Premiere, para. 35; M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, para. 66; M.7282 Liberty Global/Discovery/All3Media, para. 48; M.7360 21st Century Fox/Apollo/JV, para. 47; M.7865 Lov Group Invest/De Agostini/JV, para. 43; M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 71; M.9299 Discovery/Polsat/JV, para. 50; M.9299 Discovery/Polsat/JV, para. 50; M.10343 Discovery/Warner Media, para. 25; and M.10349 Amazon/MGM, para. 36.

-

M.7282 Liberty Global/Discovery/All3Media, para. 47.

-

M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 88.

-

M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 87.

-

M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, para. 84.

-

M.6369 HBO/Ziggo/HBO Nederland, para. 27; M.7000 Liberty Global/Ziggo, paras. 86 and 89; M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, para. 92; M.8665 Discovery/Scripps, paras. 21 and 23; M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 85; M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, para. 43; and M.10349 AMAZON/MGM, para. 54.

-

M.8354 Fox/Sky, para. 68; M.9299 Discovery/Polsat/JV, para. 50; M.10343 Discovery/Warner Media, para. 25; and M.10349 Amazon/MGM, para. 36.

-

M779 Bertelsmann/CLT, para. 18; M.1574 Kirch/Mediaset, para. 15; M.1958 Bertelsmann/GBL/Pearson TV, para. 12; M.5121 News Corp/Premiere, para. 35; M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, para. 65; M.6369 HBO/Ziggo/HBO Nederland, para. 21; M.7282 Liberty Global/Discovery/All3Media, para. 45; M.7360 21st Century Fox/Apollo/JV, para. 44; M.7865 Lov Group Invest/De Agostini/JV, para. 43; M.8354 Fox/Sky, para. 68; M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 71; M.9299 Discovery/Polsat/JV, para. 50; M.10343 Discovery/Warner Media, para. 25; and M.10349 Amazon/MGM, para. 36.

-

M.2050 Vivendi/Canal+/Seagram, para. 17.

-

M.4504 SFR/Télé 2 France, para. 32; M.5121 News Corp/Premiere, para. 35; M.5932 News Corp/BskyB, para. 65; M.6369 HBO/Ziggo/HBO Nederland, para. 21; M.8354 Fox/Sky, para. 68; M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 71; M.9299 Discovery/Polsat/JV, para. 50; M.10343 Discovery/Warner Media, para. 25; and M.10349 Amazon/MGM, para. 36.

-

M.2845 Sogecable/Canalsatelite Digital/Via Digital, para. 25.

-

M.2483 Group Canal +/RTL/GJCD, para. 19.

-

M.2483 Group Canal +/RTL/GJCD, paras. 19(a) and 19(b).

-

M.2483 Group Canal +/RTL/GJCD, para. 20. See also M.2845 Sogecable/Canalsatelite Digital/Via Digital, para. 38.

-

M.2845 Sogecable/Canalsatelite Digital/Via Digital, paras. 33 to 37; and M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiu, para. 66.

-

M.2845 Sogecable/Canalsatelite Digital/Via Digital, para. 56; and M.2876 Newscorp/Telepiu, para. 71.

-

M.9299 Discovery/Polsat/JV, para. 48.

-

M.9299 Discovery/Polsat/JV, para. 50.

-

M.7282 Liberty Global/Discovery/All3media, para. 41; M.7360 21st Century Fox/Apollo/JV, para. 40; M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, para. 69; M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 71; M.9299 Discovery/Polsat/JV, paras. 46 and 50; M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia, paras. 21 and 25; M.10349 Amazon/MGM, paras. 32 and 36.

-

M.7282 Liberty Global/Discovery/All3media, para. 35. See also M.7360 21st Century Fox/Apollo/JV, para. 38; and M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, paras. 58.

-

M.7282 Liberty Global/Discovery/All3media, para. 36; and M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, para. 58

-

M.7282 Liberty Global/Discovery/All3media, para. 37. See also M.7360 21st Century Fox/Apollo/JV, para. 38; and M.7194 Liberty Global/Corelio/W&W/De Vijver Media, para. 58.

-

M.7282 Liberty Global/Discovery/All3media, para. 37.

-

M.553 RTL/Veronica/Endemol, para. 89; M.1574 Kirch/Mediaset, para. 14; M.1958 Bertelsmann/GBL/Pearson TV, para. 11; M.7282 Liberty Global/Discovery/All3media, para. 32; M.7282 21st Century Fox/Apollo/JV, para. 37; M.9299 Discovery/Polsat/JV, para. 47; M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia paras. 20 and 21; and M.10349 Amazon/MGM, para. 30.

-

M.553 RTL/Veronica/Endemol, para. 89.

-

M.553 RTL/Veronica/Endemol, para. 90.

-

M.7282 21st Century Fox/Apollo/JV, para. 37.

-

M.553 RTL/Veronica/Endemol, para. 29. See also M.1574 Kirch/Mediaset, para. 14.

-

M.7282 21st Century Fox/Apollo/JV, para. 37.

-

M.1958 Bertelsmann/GBL/Pearson TV, para. 11; M.7282 Liberty Global/Discovery/All3media, para. 32; M.9299 Discovery/Polsat/JV, para. 47; M.10343 Discovery/WarnerMedia para. 20; and M.10349 Amazon/MGM, para. 30.

-

M.4353 Permira/All3media Group, para. 12.

-

M.1943 Telefonica/Endemol, para. 8.

-

M.1943 Telefonica/Endemol, para. 8.

-

M.8785 Disney/Fox, para. 61.

-

The future of European competitiveness – In-depth analysis and recommendations, page 299.