Monopsony in labour markets: a new enforcement priority for competition authorities

Share

Competition enforcers are increasingly interested in whether companies have buyer power, particularly in labour markets. In this article, Joe Perkins, Catalina Campillo and Gabriele Corbetta [1] review competition authorities’ recent interest and consider the tools available to avoid the risks of not acting where action is needed, or of intervening ineffectively or needlessly.

These topics were also discussed by a panel of enforcers, academics and practitioners at Compass Lexecon’s 2023 Economics Conference at Wadham College, Oxford on 22 September. This article reflects the views of the authors only.

View the PDF version of this article.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

Introduction

Purchasing power has not been front of mind for competition practitioners.[2] This is changing, particularly where it affects labour markets.

In this article, we first outline competition authorities’ growing interest in enhancing competition between employers as buyers of labour, and discuss where this interest has been demonstrated in cases and authorities’ guidelines so far. We then describe the key challenges in analysing the effects of buyer power, notably understanding the sometimes complex interaction between outcomes in labour markets and product markets. Finally, we consider the tools available to assess monopsony power rigorously, and how these tools might be augmented in coming years.

Rising concern about labour markets

In recent years, prominent economists and commentators have begun to pay greater attention to labour market power. For instance, David Card, in his 2022 presidential address to the American Economic Association, stated that “the time has come to recognize that many – or even most – firms have some wage‐setting power.”[3] The US Department of Treasury published a review of the state of labour market competition in the same year, concluding that “Lack of labor market competition contributes to high levels of income inequality, diminishes incentives for firms to invest, inhibits the creation and expansion of new firms, and reduces productivity growth through lower reallocation of labor across firms and industries.”[4]

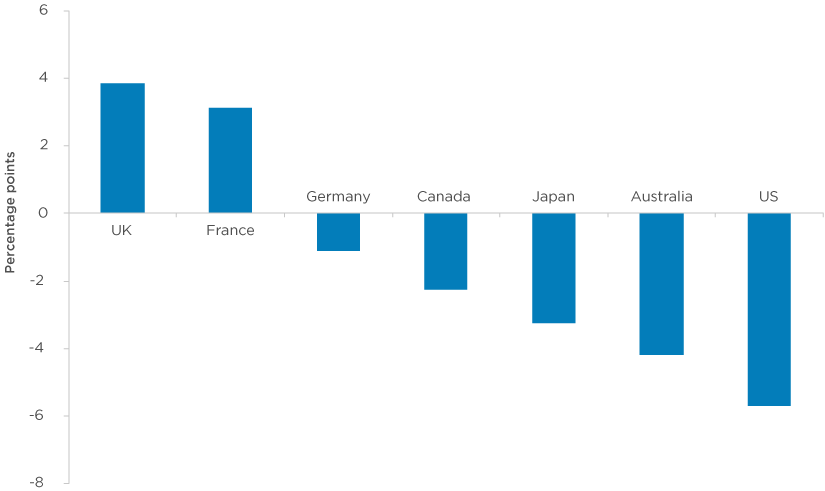

This interest reflects several factors, including the significant reductions in the share of national income received by workers in recent decades in several countries, most notably the US – see Figure 1.[5] Although some countries buck that trend, they may simply face different concerns – for example, the UK’s productivity growth has been anaemic.

Various explanations for declining labour outcomes have been proposed, of which technological advancements and globalisation are most prominent. Market concentration has also been identified as a contributing factor.[6] Some investigations of wage stagnation have called attention to the role of limited competition – both between sellers in product markets (i.e., monopoly power) and between buyers in labour markets (i.e., monopsony power).[7] [8]

Figure 1: Changes in the labour income share of gross value added across countries, percentage points, 1995-2021 (OECD)

Notes: The chart excludes non-business sectors and the primary and real estate sectors. The OECD notes that the labour share of gross value added in these sectors can in some cases not reflect well the relationship between productivity and labour; for example, because they can be skewed by large movements in commodity prices and rents or because they are affected by national accounting conventions. Additional information and figures reflecting the total economy are available from the OECD.

Source: Compass Lexecon analysis based on OECD data. OECD (2023), OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2023, Ch. 7: “Labour Income and Productivity”, Figure 7.2.

More intervention from competition authorities

These findings, combined with growing dissatisfaction in some quarters with the level of antitrust enforcement more generally, have motivated antitrust authorities to increase their interest in market power in labour markets.[9]

Policymakers are increasingly willing to use antitrust tools to promote competition for workers between employers. In particular, intervention by the US authorities – the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) and the Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) – has escalated in three areas:

- “No-poach” and wage-fixing agreements. Intervention has focussed on rival companies that used bilateral agreements to restrict their employees’ opportunities to switch to a different employer, or to fix wages. An antitrust class action of Silicon Valley workers against tech firms that agreed not to poach each other’s staff made the headlines in 2014, [10] and in 2022 the DOJ secured the first criminal prosecution relating to these practices.[11]

- “Non-compete” clauses. These interventions target companies that use employment contracts to restrict their employees’ opportunities to switch to a rival employer. In the US, this practice is common – around a fifth of US workers are estimated to be bound by these clauses.[12] In January 2023, the FTC brought cases against specific firms with non-compete clauses it deemed particularly egregious.[13] It also proposed a more ambitious intervention: a federal ban on non-compete clauses, on the basis that they are an “unfair method of competition” which can suppress wages and innovation.[14]

- Mergers that increase buyers’ power. The most recent developments have taken place in the context of merger reviews. In July 2023, the FTC and DOJ published updated draft Merger Guidelines [15] discussing the effects of mergers in both output markets and input markets – emphasizing that attention to input markets should also extend to labour markets. The draft Guidelines are not a complete departure from their predecessors, which already discussed competition in input markets, but did not explicitly highlight labour.[16] Those guidelines still enabled US enforcers to consider the impact of mergers on labour markets, as they did for example in challenging the proposed merger between Penguin Random House / Simon & Schuster.[17] But the new draft Guidelines suggest a shift in priorities.

In Europe, there has been less intervention, perhaps because labour market protections are in general stronger than in the US. Nonetheless, the appetite for intervention is growing. In the EU, Commissioner Vestager recently discussed the anticompetitive effects of no-poach agreements, restricting the free movement of talent and indirectly dampening wages.[18] The latest guidelines on cooperation agreements between competitors emphasise that agreements to fix wages could be prosecuted as a buyer cartel.[19] There is also increasing action at national level. Several member states have brought cases against bilateral agreements between buyers in input markets.[20] Portugal is making competitive labour markets one of the competition policy priorities for 2023.[21]

The UK takes a similar stance. The Competition and Markets Authority (“CMA”) has stated that concerns about competition in labour markets “could have significant implications for the types of cases the CMA pursues, and how it builds a theory of harm”, and that it plans to examine competition issues within UK labour markets.[22] However, labour market concerns have not thus far been a primary motivation for intervention in mergers by either the EC or the CMA.[23]

The complex effects of buyer power on consumers

At first sight, antitrust authorities’ concerns about buyer power may seem counterintuitive. Buyer power should – intuitively – reduce input prices, which would benefit consumers if those savings are passed on to some extent. In some cases, that is true. But the effects of buyer power are ambiguous and often more complicated.

To understand these effects, it helps to consider how monopsony works. Broadly, buyer power can affect market outcomes in two ways.

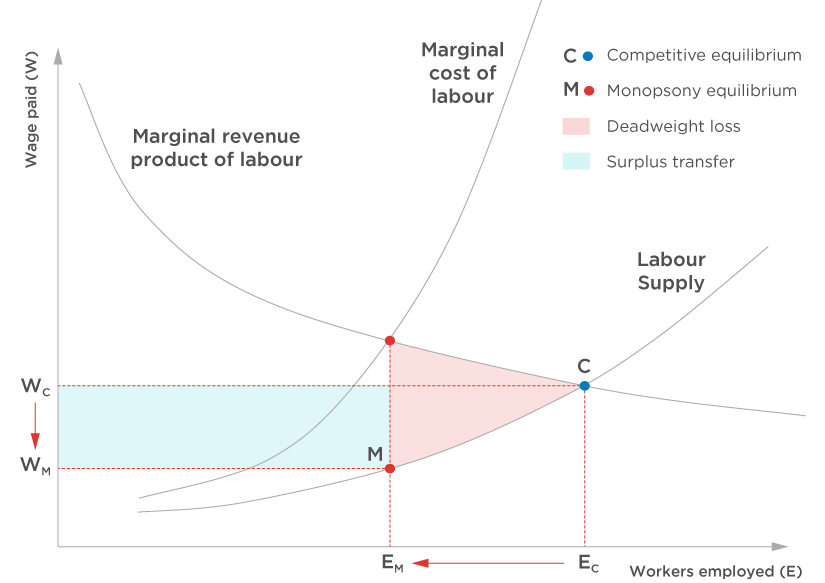

- The “classical” monopsony mechanism.[24] Purchasers with monopsony power reduce the price they pay for each unit of input by reducing the quantity they purchase below the competitive level, as shown in Figure 2.

- Distorting bargaining leverage. If prices are set via negotiation between buyers and sellers, consolidating the buyer side of the market (for example, via mergers or cartels) can reduce sellers’ “outside option” – the alternative they could fall back on if negotiations fail. This could result in a reduction of the price paid by buyers without any change in the quantities they buy.

Figure 2: The “classical” monopsony mechanism: reducing input purchases to reduce input prices

Notes: The chart shows how the “textbook model” of how the competitive market equilibrium (C) compares to the monopsony equilibrium (M) in inputs market – using labour as an example. In the competitive equilibrium, wages and the number of workers employed match the marginal revenue product (MRP) of labour (that is, the additional revenue created by the firm when employing one additional employee) to the labour supply curve (that relates the wages paid to the level of employment). In the monopsony equilibrium, the firm employs fewer workers – up to the level where the MRP of labour matches the marginal cost (MC) of labour (that is, the cost of employing one additional worker) and pays each worker a lower wage. This results in a transfer of economic surplus from workers to the firm and in an overall economic inefficiency, or deadweight loss, compared to the competitive equilibrium. See Manning, A. (2003), “Monopsony in Motion: Imperfect Competition in Labor Markets”, Princeton University Press, pp. 30-31.

The “classical” monopsony mechanism will often harm consumers as well as workers. When purchasers with buyer power reduce their purchases of inputs to drive down their price, that can lower the overall quantity (or quality) of the output they offer in the market. If the purchasers also have (product) market power, the lower quantity produced can cause output prices to increase. This further increases producers’ profits and decreases consumers’ welfare. Buyer power could also harm consumers in the longer term, for instance if it reduces incentives to supply in the future.[25]

However, buyer power may have positive effects on consumers if it distorts bargaining leverage.

First, if it lowers input costs without restricting output in the product market – because, crucially, downstream competition is not restricted – then those savings are likely to be passed on to consumers, benefiting them at least in the short term.[26]

Second, buyer power can also help neutralise market power that already exists on the seller side of the market (“countervailing buyer power”), which could lower prices for consumers. Crucial factors are the size and commercial significance of the buyers and their ability to switch to other suppliers, vertically integrate, or sponsor entry or expansion of other suppliers.[27] A key example is the Enso / Stora merger of two large suppliers of liquid packaging board. In 1998, the EC found that this merger would not result in these suppliers acquiring or strengthening a dominant position because of buyer power from highly concentrated purchasers. Similar considerations motivated in part the EC’s decision to clear, seven years later, another merger between suppliers in the same market, Korsnäs / AD Cartonboard.[28]

Although protecting competition for the benefit of consumers is the main goal of competition policy in many jurisdictions, the direct effect of conduct on consumers is not all that counts. For example, the EU aims to protect competition in the internal market from distortions – on the basis that there is value in protecting the structure of the market and competition “as such”, even when distortions do not have a detectable impact on final consumers.[29] In the US, the draft Merger Guidelines indicate that benefits to competition among sellers will not in principle “save” mergers that harm competition among buyers.[30] In other competition regimes, notably South Africa, public interest considerations play a much larger role in competition law.[31] In these cases, additional objectives – and not only the direct impact of conduct on consumers – may be considered by authorities.

Why does labour monopsony matter for competition policy?

So far, we have discussed buyer power in general, without any differentiation between whether buyers are purchasing widgets or the time of employees. But there are some reasons to think that labour market monopsony may be of particular interest for competition policy.

First, and most obviously, we may care more about the interests of workers than about, for instance, firms that provide car parts.[32] Most countries have regulations that protect the rights of workers to bargain collectively, and try to influence labour market outcomes in many ways, including through employment protection rights and minimum wages. In this context, it may seem odd if competition authorities were only to care about outcomes for workers to the extent that consumers were also affected.

Second, monopsony power in labour markets could have long-term consequences on labour supply and output markets. In labour markets, skilled professions require upfront investments in time and money to train. Buyer power could make employees reluctant to make such investments as their returns will be limited by what firms are prepared to pay.[33] Conversely, however, strong competition between firms for employees could make employers reluctant to invest in their employees’ skills, as they fear losing them as soon as they have been trained.[34]

Third, certain characteristics of labour markets may make them particularly susceptible to buyer power. For example:

- Fragmented suppliers. Labour markets can be highly fragmented, with a much more concentrated “buying” side (employers) compared to the ”selling” side (workers). This can put workers in a weak negotiating position. An extreme case which the EC recently assessed relates to “solo self-employed workers”, for example those providing services to digital platforms as riders.[35]

- High switching costs. Most workers face greater barriers than other ”suppliers” when it comes to switching who they supply. Workers tend to ”supply” only one employer at a time, so they are more exposed to switching costs. Moreover, the costs of switching can be high, particularly when it involves moving to an alternative location for work: people’s investments (e.g., purchasing a home) and individual needs (e.g., enrolling their children at school) are often specific to a location and not easily “portable”.

- High search frictions. The process of finding and starting a new job can also have large frictions: workers will need to gather information to evaluate alternative employers, and will spend time and effort to go through the recruitment process and training. Risk aversion may also play a role in increasing barriers for workers to search for and accept a different position.[36] Alan Manning notes that “people go to the pub to celebrate when they get a job rather than greeting the news with the shrug of the shoulders that we might expect if labor markets were frictionless. And people go to the pub to drown their sorrows when they lose their job rather than picking up another one straight away.”[37]

- Matching process between workers and employers. “Matching” the complex preferences of workers and employers reduces the number of options for workers.[38] Workers value several dimensions of a profession – not all of which relate to wages: for example, working conditions, the type and variety of assignments, etc. Other input sellers are unlikely to have similarly multi-faceted preferences on the characteristics of the buyers as workers have for employers. Different employers hiring for the same position can also have specific requirements for workers’ characteristics – from their level of education, experience and skills, to potentially more nebulous concepts such as attitudes and cultural fit.[39]

These characteristics often arise in labour markets, but they are not unique to them – other input markets can have similar features. Fragmentation on the seller side is common in various agricultural markets – such as fragmented animal farmers faced with concentrated meat processors. Switching costs and matching frictions can arise in input markets, for example, when a supply relationship requires technically demanding and costly investments specific to the requirements of a buyer.[40]

Further, these characteristics are not inherent to all labour markets. Collective bargaining can mitigate the fragmentation of workers vis-à-vis employers. Certain categories of workers can choose from only a limited number of potential employers, while others have more options. The prevalence and impact of these frictions need to be analysed in each case. This makes it challenging for competition authorities to identify and prevent the negative effects of buyer power.

The challenges of intervening to tackle buyer power

Historically, intervention by authorities to tackle buyer power has been rare compared with action to prevent distortion in product markets. In part, that is because it is much more challenging to unpick the ambiguous and complex effects of buyer power.

Enforcement has been most common where an analysis of the effects of buyer power is not required.[41] In particular, the EC has pursued several cases against cartels where buyers coordinated on purchase prices. In these cases, the EU courts do not require the Commission to demonstrate effects on competition or final consumers.[42] Rather, price-fixing agreements between buyers are prohibited “by object”, just like cartels between sellers: the type of conduct revealed in itself a sufficient degree of harm to competition that the EC did not need to demonstrate anticompetitive effects as well. In “by object” cases the conduct is considered to have such a potentially restrictive – rather than ambiguous – effect on consumers (and / or on the structure of the market and competition “as such”) that a full analysis of its effects is unnecessary.[43]

However, as a matter of economics, the ambiguous effect of monopsony means that few agreements between buyers should fall into this “by object” category. Effectively, they must act as a “disguised cartel” – for example, fixing prices, limiting output, allocating markets, or exchanging highly sensitive information on purchasing intentions and negotiations with suppliers.

In most cases, a closer analysis is required to untangle potentially ambiguous effects. For example, the EC guidelines on purchasing agreements acknowledge their possible pro-competitive effects – they can “lead to lower prices, more variety or better quality products for consumers”, enable better purchasing terms, and help avoid disruptions in the supply chain – but they can also give rise to competition concerns.[44] Similarly, non-compete clauses can have pro-competitive effects if they enable firms to train employees or share confidential information without the fear of competitors taking advantage of their efforts. But they can also be a tool to reduce competition between employers; and alternative, less restrictive options, such as non-disclosure agreements, can in certain cases be used to achieve the same pro-competitive effects.[45]

When an effects analysis is required, strong interventions motivated by buyer power have been less common. For instance, even though the EU Merger Regulation recognizes the role of buyer power – requiring the EC to take into account factors including “the alternatives available to suppliers”[46] – in practice, few merger decisions depend on an analysis of buyer power in input markets.[47]

Overcoming the challenges

As the appetite to address buyer power increases, including in labour markets, there will be a greater need to analyse the markets in which it arises and assess its impact. Given the challenges of analysing the ambiguous effects of monopsony, competition authorities face two risks: either (continuing) not to enforce where anticompetitive effects are likely to occur; or enforcing ineffectively – in cases where adverse effects are unlikely, or without a rigorous understanding of the effects.

The economic tools are available

The key economic question in the analysis of buyer power is the same as it is in product markets: substitution. Which alternative buyers (employers) would the sellers (workers) consider if competitive conditions in the labour market degrade – and in which locations? This helps delineate the boundaries of competition for labour and the immediate constraints that employers face. In other words – defining relevant labour markets and identifying the competitive constraints that companies face.

The frameworks and tools to address the equivalent questions in product markets are well-established, to determine rigorously how substitution affects the competitive constraints on firms.

These can be adapted relatively easily to analyze labour markets. For instance, to define labour markets from an antitrust perspective, the US draft Merger Guidelines suggest adapting the standard “Hypothetical Monopolist” test: authorities would consider whether a hypothetical monopsonist would find it profitable to apply at least a “small but significant and non-transitory increase in price or other worsening of terms” (“SSNIPT”), such as a “decrease in the wage offered to workers or a worsening of their working conditions or benefits” compared to a competitive outcome.[48] Are workers able to switch in response to a SSNIPT, making it unprofitable for an employer – and which locations or alternative employers would they consider?

In product markets, this framework tends to guide analysis in principle, rather than in practice. Instead, precedent, intuition, and convention often determine market definition, rather than a rigorous analysis of substitution.[49] However, those conventions and shortcuts may be unavailable to guide analysis of substitution in labour markets. Precedent is scarce, and intuition and convention will not reflect the less familiar forces that determine substitution in labour markets.

An illustration: assessing local competition in practice

To illustrate how analyses on product market substitution can be applied to labour markets, consider the case of a merger between, say, the two hospitals in a city. Its effects on labour markets – whether it increases buyer power, and against which categories of workers – depends on the alternative employers available to workers in locations they can reach.

Local competition is typically of the essence in labour markets – as it is in certain product markets, such as physical retail – given the switching costs and frictions involved in workers moving to a different location. The boundaries of local competition depend on workers’ willingness and ability to commute to alternative employers following a hypothetical deterioration in labour conditions. This will differ case by case: in some locations, and for some professions, alternative employers may be densely concentrated in a local area – in other cases, workers may have to travel far. It also depends on which means of transportation are available and accessible to workers.

Geospatial analysis tools – increasingly used in the analysis of product markets – can facilitate the assessment of workers’ ability to reach different employers. These tools use data science techniques to collect and link geographic and business data – such as the location of different employers – to data on means of transportation and commuting times.[50] This can help define catchment areas based on travel distance (or “isochrones”).

The question of hypothetical diversion following a SSNIPT – the alternatives workers would choose – also depends on workers’ willingness to consider different locations, not just their ability to do so. Ways to measure this include survey evidence – testing workers’ choices in a hypothetical scenario. Other evidence includes the current commuting time and distance of workers, and diversions to alternative employers and locations following “natural experiments” such as a firm closing down.

Another dimension relates to the rival industries, occupations and employers that workers are able, and willing, to consider. Again, this requires a case-by-case assessment. Certain occupations rely on skills that are highly industry-specific; others do not. For example, doctors are tied to the medical sector, while HR professionals are more likely to find similar employment across a variety of industries. Retraining for a slightly different, but closely related, occupation may be difficult in certain cases – say, in case of high barriers from certification and licensing requirements – while it may be straightforward in others. Simply relying on standardized industry or occupation codes – the approach taken by many economic studies of concentration in labour markets – is not enough for a competition case. Again, survey evidence on hypothetical substitution and historical evidence on diversion can prove helpful.

Analysing long-term dynamic effects will also be important to a competitive assessment of labour markets – to a greater extent in some cases than others. Existing workers may be unable or unwilling to move locations or to switch to alternative occupations when employment conditions deteriorate. But, in the long term, it may become more difficult to retain existing workers and attract new ones.

Conclusion

Competition authorities are increasingly interested in competition in labour markets, responding to wider concerns about perceived poor outcomes for workers. However, with few previous cases to draw upon, it is particularly important that analysis of any competitive effects is firmly grounded in rigorous evidence and economic theory. There are some existing tools that could be adapted for this purpose, such as survey evidence on hypothetical substitution, but more research is needed to understand how, for instance, different groups of workers perceive their switching possibilities. Ex post evaluations of any enforcement actions – and of cases where authorities opt not to intervene – will help to build expertise and ensure balanced, effective enforcement. A transparent and rigorous analytical framework should help to avoid the risks of not taking action where action is needed, of intervening ineffectively, or of mistargeting intervention.

Read all articles from this edition of the Analysis

View the PDF version of this article.

[1] Joe Perkins is a Senior Vice President and the Head of Research at Compass Lexecon. Catalina Campillo is a Vice President at Compass Lexecon. Gabriele Corbetta is an Economist at Compass Lexecon. The authors thank Elena Zoido, Allen Huang, Lars Martinez Ridley, Andrew Tuffin, and Benoit Voudon for their comments. The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

[2] CMA (2023), “CMA Economic Research Strategy”, para. 4.11.

[3] Card, D. (2022), “Who Set Your Wage?”, American Economic Review, Vol. 112(4): 1075-1090.

[4] U.S. Department of the Treasury (2022), “The State of Labor Market Competition”, p. ii.

[5] Karabarbounis, L. and B. Neiman (2014), “The Global Decline of the Labor Share”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 129(1): 61-103; IMF (2017), “World Economic Outlook: Gaining Momentum”, Ch. 3: “Understanding the Downward Trend in Labor Income Shares”, pp. 121-173; Autor, D., D. Dorn, L. Katz, C. Patterson, and J. Van Reenen (2020), “The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 135(2): 645-709, and references therein.

[6] Marinescu, I., I. Ouss, and L.-D. Pape (2021), "Wages, hires, and labor market concentration”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Vol. 184: 506-605; Azar, J., I. Marinescu, and M. Steinbaum (2022), “Labor Market Concentration”, Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 57(S): S167–S199; Benmelech, E., N. K. Bergman, and H. Kim (2022), “Strong Employers and Weak Employees: How Does Employer Concentration Affect Wages?”, Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 57(S): S200-S250; Prager, E. and M. Schmitt (2019), “Employer Consolidation and Wages: Evidence from Hospitals”, American Economic Review, Vol. 111(2): 397-427.

[7] Deb, S., J. Eeckhout, A. Patel, and L. Warren (2022), “What Drives Wage Stagnation: Monopsony or Monopoly?”, Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 20(6): 2181-2225.

[8] There is no consensus. For example, see OECD (2020), “Competition in Labour Markets”, p. 3; Grossman, G. M. and E. Oberfield (2022), “The Elusive Explanation for the Declining Labor Share”, Annual Review of Economics, Vol. 14: 93-124.

[9] See e.g., US Executive Order 14036 (2021), “Promoting Competition in the American Economy”, 86 FR 36987, which states the U.S. administration’s intention to enforce antitrust laws against “the harmful effects of monopoly and monopsony — especially as these issues arise in labor markets”. See also remarks of FTC Chair L. M. Khan (2021), “Making Competition Work: Promoting Competition in Labor Markets”, Joint Workshop of the FTC and DOJ; statement of FTC Commissioner A. M. Bedoya, joined by Chair L. M. Khan and Commissioner R. K. Slaughter (2023), “Regarding the Proposed Merger Guidelines Issued by the Federal Trade Commission & U.S. Department of Justice”.

[10] Elder, J. (2014), “Tech Companies Agree to Settle Wage Suit”, The Wall Street Journal, 24 April.

[11] Gibson Dunn (2022), “DOJ Antitrust Secures First Conviction for No-Poach and Wage-Fixing Conduct”, 31 October.

[12] Starr, E. P., J. Prescott, and N. D. Bishara (2021), “Noncompete Agreements in the US Labor Force”, The Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 64(1): 53-84.

[13] In one of these cases, the FTC alleges that security guards signed non-compete agreements preventing them from working for a competing business within a 100-mile radius after leaving their company, subject to a $100,000 penalty. See FTC (2023), “FTC Cracks Down on Companies That Impose Harmful Noncompete Restrictions on Thousands of Workers”.

[14] FTC (2023), “FTC Proposes Rule to Ban Noncompete Clauses, Which Hurt Workers and Harm Competition”.

[15] FTC and DOJ (2023), “FTC-DOJ Merger Guidelines (Draft for Public Comment)”.

[16] FTC and DOJ (2010), “Horizontal Merger Guidelines”, pp. 32-33.

[17] DOJ (2022), “Justice Department Obtains Permanent Injunction Blocking Penguin Random House’s Proposed Acquisition of Simon & Schuster”.

[18] Speech of EC Executive Vice-President M. Vestager (2021), “A new era of cartel enforcement”, Italian Antitrust Association Annual Conference.

[19] EC (2023), “Guidelines on horizontal co-operation agreements”, para. 279.

[20] Remaly, B. (2021), “Hungary fines recruitment association for price-fixing and no-poach agreements”, Global Competition Review, 8 January; Competition Council of the Republic of Lithuania (2020), “Konkurencijos Taryba launches investigation into suspected anti-competitive agreement among Lithuanian Basketball League and basketball clubs”; Bundeskartellamt (2016), “Bundeskartellamt verhängt Bußgelder gegen Fernsehstudiobetreiber”. Outside the EU, see Masson, J. (2022), “Swiss enforcer targets banking sector in first labour markets probe”, Global Competition Review, 5 December.

[21] Autoridade da Concorrência (2022), “Competition Policy Priorities for 2023”.

[22] CMA (2023), “CMA Economic Research Strategy”, para. 2.2, 4.11, 4.12. See also plans to examine potential competition issues in UK labour markets in 2023-2024: CMA (2023), “Competition and Markets Authority Annual Plan 2023/2024”, p. 24.

[23] See e.g., Araki, S., A. Bassanini, A. Green, L. Marcolin, and C. Volpin (2023), “Labor Markets Are the New Frontier for Competition Policy”, Promarket, 28 July, and “Labor Market Concentration and Competition Policy Across the Atlantic”, The University of Chicago Law Review, Vol. 90(2): 339:378.

[24] See e.g., Ashenfelter, O. C., H. Farber, and M. R. Ransom (2010), “Labor Market Monopsony”, Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 28(2): 203-210; Tong, J. and C. Ornaghi (2022), “Joint Oligopoly-Oligopsony Model with Wage Markdown Power”, University of Southampton Discussion Paper 2101; Hemphill, C. S. and N. L. Rose (2018), “Mergers that Harm Sellers”, The Yale Law Journal, Vol. 127(7): 2078-2109.

[25] See e.g., OECD (2008), “Policy Roundtables: Monopsony and Buyer Power”, p. 10; Hemphill, C. S. and N. L. Rose (2018), “Mergers that Harm Sellers”, The Yale Law Journal, Vol. 127(7): 2078-2109.

[26] EC (2004), “Guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers under the Council Regulation on the control of concentrations between undertakings”, para. 61-63.

[27] EC (2004), “Guidelines on the assessment of horizontal mergers under the Council Regulation on the control of concentrations between undertakings”, para. 64-67.

[28] Case M.1225, Enso / Stora, para. 97, 100. Case M.4057, Korsnäs / AD Cartonboard, para. 43-53. Ezrachi, A. and M. Ioannidou (2014), “Buyer Power in European Union Merger Control”, European Competition Journal, Vol. 10(1): 69-95. Anchustegui, I. H. (2017), “Buyer Power in EU Competition Law”, The University of Bergen, pp. 471-475.

[29] See e.g. Case C-8/08 T-Mobile Netherlands And Others, Opinion of Advocate General Kokott (2009), para. 55-60, and Judgment of the Court (Third Chamber) (2009), para. 36-38.

[30] FTC and DOJ (2023), “FTC-DOJ Merger Guidelines (Draft for Public Comment)”, p. 26. Similar points were made in the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines: see DOJ and FTC (2010), “Horizontal Merger Guidelines”, pp. 32-33.

[31] See e.g. Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr (2022), “In the public interest: No longer negotiable”.

[32] There have though been some antitrust interventions to protect the interests of small suppliers in disputes with large purchasers. For example, in the UK the Groceries Code Adjudicator (the “Supermarket Ombudsman”) is responsible for reviewing disputes between the largest grocery retailers and their suppliers.

[33] Hemphill, C. S. and N. L. Rose (2018), “Mergers that Harm Sellers”, The Yale Law Journal, Vol. 127(7): 2078-2109, p. 2083; Bassanini, A. and Ok, W. (2004), “How do firms’ and individuals’ incentives to invest in human capital vary across groups?”. Blundell, R. and T. Macurdy (1999), “Labour supply: A review of alternative approaches”, Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. 3, Part A, Ch. 27, p. 1679.

[34] Posner, E., A. Triantis, and G. G. Triantis (2004), “Investing in Human Capital: The Efficiency of Covenants Not to Compete”, Univ. of Virginia Law & Econ Research Paper No. 01-08; Mecchieri, N. (2009), “A note on noncompetes, bargaining and training by firms”, Economic Letters, Vol. 102(3): 198-200; Shy, O. and Stenbacka, R. (2022), “Noncompete agreements, training, and wage competition”, Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, Vol. 32(2): 328-347.

[35] EC (2022), “Guidelines on the application of Union competition law to collective agreements regarding the working conditions of solo self-employed persons”. See esp. para. 8, 17 (example 1), and 28.

[36] van Huizen, T. and R. Alessie (2019), “Risk aversion and job mobility”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Vol. 164: 91-106.

[37] Manning, A. (2003). “Monopsony in Motion: Imperfect Competition in Labor Markets”, Princeton University Press, p. 3. OECD (2020), “Competition Issues in Labour Markets”, p. 22.

[38] FTC and DOJ (2023), “FTC-DOJ Merger Guidelines (Draft for Public Comment)”, pp. 25-27. OECD (2020), “Competition in Labour Markets”, p. 22. Naidu, S. and E. A. Posner (2022), “Labor Monopsony and the Limits of the Law”, Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 57(S): S284-S323, p. S300.

[39] Manning, A. (2011), “Imperfect competition in the labor market”, in D. Card and O. Ashenfelter (eds.), Handbook of labor economics, Vol. 4b: 973-1041, pp. 976-978.

[40] See e.g., OECD (2008), “Policy Roundtables: Monopsony and Buyer Power”, pp. 66 and 218.

[41] For an overview of historical enforcement and recent developments, see OECD (2022), “Purchasing Power and Buyers’ Cartels – Note by the European Union”, section 2.

[42] OECD (2022), “Purchasing Power and Buyers’ Cartels – Note by the European Union”, para. 11.

[43] See e.g. Case C-8/08 T-Mobile Netherlands And Others, Opinion of Advocate General Kokott (2009), para. 42-43 and 55-60, and Judgment of the Court (Third Chamber) (2009), para. 28-29 and 36-38.

[44] EC (2023), “Guidelines on horizontal co-operation agreements”, section 4.2.

[45] See e.g., Mecchieri, N. (2009), “A note on noncompetes, bargaining and training by firms”, Economic Letters, Vol. 102(3): 198-200; Posner, E., A. Triantis, and G. G. Triantis (2004), “Investing in Human Capital: The Efficiency of Covenants Not to Compete”, Univ. of Virginia Law & Econ Research Paper No. 01-08.

[46] Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 (EU Merger Regulation), Art. 2.

[47] Ezrachi, A. and M. Ioannidou (2014), “Buyer Power in European Union Merger Control”, European Competition Journal, Vol. 10(1): 69-95. Anchustegui, I. H. (2017), “Buyer Power in EU Competition Law”, The University of Bergen.

[48] FTC and DOJ (2023), “FTC-DOJ Merger Guidelines (Draft for Public Comment)”, appendix 3.

[49] Padilla, J., J. Perkins, and S. Piccolo (2023), “Market definition in merger control revisited“, in I. Kokkoris and N. Levy (eds.), “Research Handbook on Global Merger Control”, Edward Elgar. See also Perkins, J. (2021) “Market definition in principle and practice”, The Analysis, Compass Lexecon.

[50] See Kocanova, I., J. Forster, and T. Howard (2023), “A taste of geospatial analysis for competition economics”, Compass Lexecon.