Testing, testing...

Share

In the recent dispute between Spotify and Apple, Random Control Tests – also known as A/B tests in the tech sector – provided competition authorities with compelling evidence of alleged misconduct. John Davies, Peter Bönisch, and Rashid Muhamedrahimov explain the advantages of this approach (the main proponents of which have recently been awarded the Nobel Prize in economics) and the circumstances in which it can suitably be applied in competition cases.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees or its clients.

Competition cases are rarely if ever decided by a single piece of economic evidence, so parties and agencies need to consider many sources. Recently, some cases have featured evidence from Randomized Control Trials (RCTs, also called A/B tests or simply ‘experiments’), developed in the tech sector to test the effect of new or alternative features on customer behavior – or simply changes in prices – on a representative group of users.

For example, when Spotify complained to the European Commission about Apple’s App Store practices, it reported the results of a trial in which many thousands of users on Android had received a Spotify app designed to mimic the more constrained functionality of Spotify’s iOS app. By comparing subscription rates from this ‘treatment’ group and the ‘control’ group of otherwise identical users of the ordinary Android app, Spotify estimated the effect of Apple’s restrictions on its subscriptions.

In principle, a well-designed experiment can directly isolate the effect being studied more simply than statistical techniques that seek to remove confounding factors from historical data. In that respect they are like surveys, but (unlike surveys) they measure actual behavior, not responses to questions about behavior.

However, experiments will not be suitable for all cases and are never a perfect solution. They must be well-designed, with a good understanding of how the measured behavior actually relates to the economics of the competition case. Furthermore, the process and data handling must conform to competition authority expectations of good practice if the results are to be accepted. Such experiments must therefore be conducted with the full involvement of competition economists and lawyers, to make the best use of them in a competition case.

Randomized control trials

RCTs are common in medical testing. Some group of patients is provided with a ‘treatment’ and its outcomes compared with a ‘control’ group of other patients which is not provided with the treatment (although the control group often receives an identical-looking placebo, to make the experiences of the two groups as similar as possible and avoid patients and medical personnel guessing which group is which).

It is rarely possible in economics to conduct experiments of that kind. Instead, usually economists must study some historical event. The price of pencils went up: did many consumers switch to using pens? The main problem with such studies is that other – observable or even unobservable – factors will have affected the demand for pens and pencils. Economists use econometrics – statistical techniques – to try to correct for this, but the results can often be ambiguous and hard to explain to non-specialists. More fundamentally, causation may be unclear: did the price of pencils rise because of some other events (such as the start of the school year) that might also have affected the demand for pencils and pens through other channels? Sometimes economists get lucky and there is a clear ‘control’ – such as another country in which the price change did not occur while the ‘other events’ did – but such ‘natural experiments’ are rare and there may still be concerns, for example, that the other country is not comparable.

Economists have also occasionally tested behavior in ‘lab’ conditions, in which participants are faced with economic decisions. Treatment and control groups can be established but there are often differences between these settings and the real world: participants are typically students and the sums at stake might add up to $100 or so.

An alternative approach, much used by businesses and more recently, governments, is to conduct ‘trials’ of new products, price changes, or policies. For example, a grocery retailer might offer a discount scheme in some supermarkets, that is not available in others, and study the effects. The results will be more reliable, the more the trial can be set up so that the ‘treated’ supermarkets and the ‘control’ supermarkets are identical in all respects except for the discount scheme being tested. Policies can also be trialed, for instance, ‘microcredit’ loans could be made available to some farmers in developing countries and not others, and the results tracked. The 2019 Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to researchers “for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty”, who had used RCTs to test what works and what does not in development economics (a field that used to be long on ideology and grand theories and short of specific evidence).[2]

Tech companies make much more use of such trials – A/B tests are often used to drive a very large share of decision-making. This can be either on “digital” aspects of the business, such as website design choices (for example, making certain purchase options more prominent), or “real” aspects of the business (such as changing the price of a product).[3] One reason for this is speed and cost: prices or other terms on a website can be changed very quickly and the results monitored in real-time. This is enabled by both the nature of the business but also the infrastructure that underlies it. Another is the economics of scale and effect size: many choices might have very small individual effects, which are only important because of the large number of users.

Creating different groups of users online does not quite solve the problem of how to ensure that treated users are randomly selected and otherwise identical to the untreated ‘control’ group but it helps: unlike users of supermarkets, for example, the users of online services do not have to be in different towns or stores in order to be allocated into different groups.

To date, such techniques have rarely been used to provide evidence for competition cases, but in some industries at least it has great potential to supplement more traditional sources of evidence. We at Compass Lexecon have seen some examples in the last few years and expect to see more.

Assessing the effects of conduct

One prominent example derives from Spotify’s complaint to the European Commission about Apple’s conduct in rules governing its App Store that led to an investigation that is ongoing at the time of writing.[4] We will not summarise the entire case, but at its core was Apple’s requirement that users ‘converting’ from Spotify’s Free service to Premium (taking out a subscription) in the Spotify app on iOS (iPhone or iPad) must use Apple’s own payment mechanism, which meant they would pay a higher price that includes Apple’s commission (now 30% in the first year of subscription, 15% from the second year). Users could convert anywhere – for example, on Spotify’s website, in any browser on a PC or even on a phone, for example – and evade this requirement. Those users would pay a lower price) and still be able to use the Premium service on their app on the iPhone. However, not only did Apple prevent the direct use of alternative payment mechanisms in the app, it also prevented app developers from including messages or links in the app to steer users to alternative channels, such as Spotify’s website. Spotify had itself removed in-app sign-up from its iOS app but remained subject to these ‘anti-steering’ restrictions.[5]

The complaint related only to Apple. Although Google had some similar policies in place governing Android apps, they were less restrictive and Spotify was able to include a ‘buy button’ in the Android app that allowed sign-up without using Google Pay.

Spotify’s complaint provided several pieces of evidence that these policies had materially harmed its business by reducing the number of subscribers in iOS, compared to a counterfactual in which these restrictions were not in place. These included two experiments.

- In the first of these, Spotify created an iOS-style variant of its app for a randomly selected 10% of all new users downloading its app on Android. It then tracked how many converted to Premium during and after its biannual promotional campaign, compared with the ‘control’ group receiving the regular app.

- In the second, conducted six months later at the next promotional campaign, Spotify ran an experiment with three treatment groups. Two imposed some but not all of Apple’s restrictions, while the third was the full ‘iOS-style app’, again compared with a control group receiving the ordinary Android app. This was to help understand which aspects of Apple’s interlocking restrictions were the most important (which could also help guide the European Commission’s thinking on remedies).

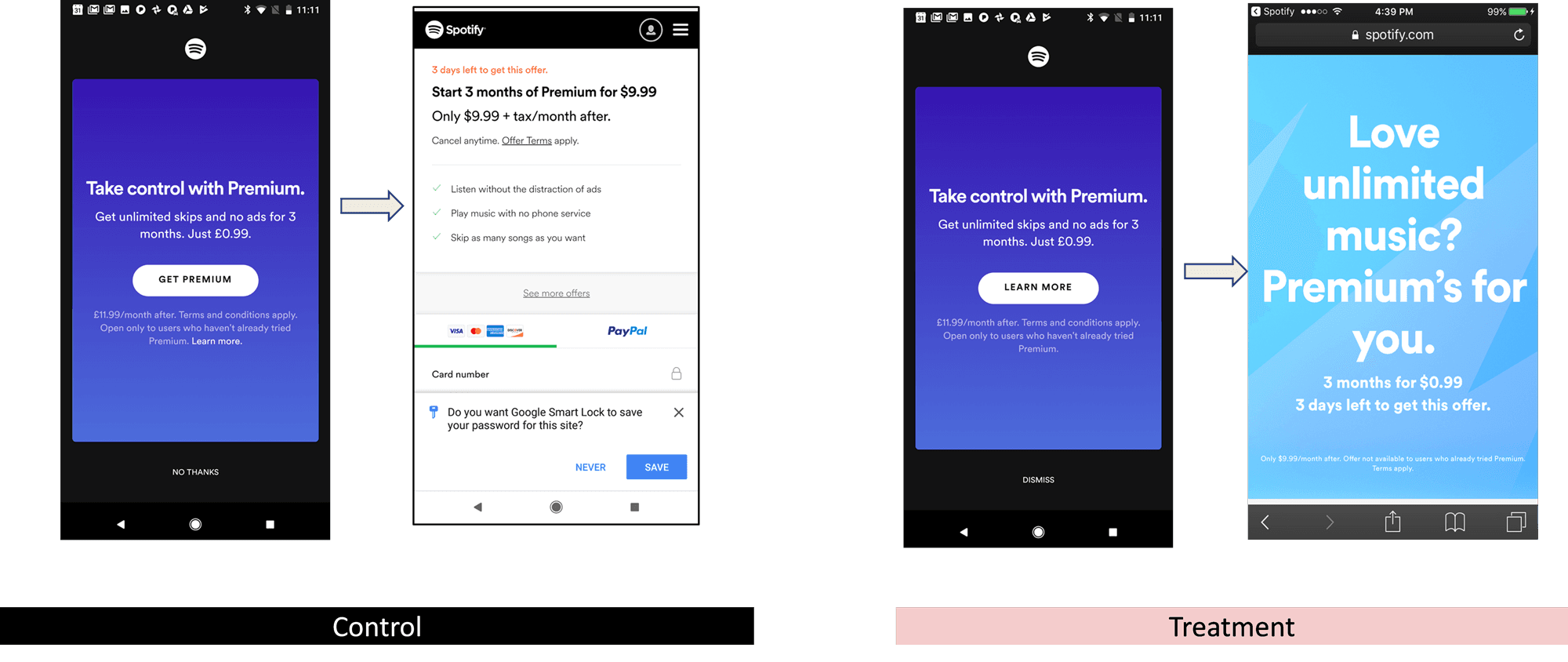

The screenshots in Figure 1 show some examples. On the left is the control group: it shows the in-app screen an Android user would see after responding to Spotify’s promotional message, with options to subscribe. On the right is the more generic screen that would be available to an iOS user, but in this experiment was presented to the ‘treatment group’ as a modified app within Android. Although the user can still subscribe to Premium, almost no information is provided about how to do so, in line with Apple’s rules.

Figure 1: Example control and treatment group screenshots

Source: Spotify

The experiments were on a large scale: over 600,000 people in five countries in the first, of which about 60,000 received the ‘treatment’ and just over 1,000,000 people in nine countries in the second, with about 200,000 in each of the three treatment groups. This large scale was important because – as is often the case in online markets – the differences were small as a proportion of the total. Most Spotify users do not subscribe, so a difference of a few percentage points in the number who do makes a material difference to the business.

The results of the two experiments are confidential, but in each case, some quite small differences between the treatment and control groups – showing the isolated effects of Apple’s restrictions – translated into sufficiently large numbers of lost subscribers to be statistically significant at any level. Furthermore, the numbers were large enough to be economically significant, in that the loss in subscription numbers materially harmed Spotify’s scale and profitability (as experts at Compass Lexecon demonstrated using the results in a financial model).

The European case is not concluded at the time of writing but these experimental results are likely to have been influential in demonstrating the effects of Apple’s conduct.

Lessons for applying experiments in competition cases

Where they can be carried out, experiments can be useful in many aspects of competition cases. The experiments above focused directly on conduct but many firms run tests on price variations in a way that could be useful to determine elasticities and diversion, or to assess competitive constraints and market definition, for example. At the other end of the case, experiments can be used to road-test remedies.

However, this technique is not a panacea. Like any empirical method, it must be designed well to suit the purpose of the case, it must be carried out properly, the results must be interpreted carefully and correctly, and any limitations in its applicability to the case must be explained. Even firms experienced in running such experiments should fully involve their advisory competition economists and lawyers when planning and running experiments for competition cases (just as very experienced market research firms need such guidance when running surveys for competition cases). It is a very different exercise from producing and communicating results for internal business purposes.

Firstly, an experiment must test something of relevance to the economics of the case. If, for example, substitution to other products is something that takes place over time, then an experiment showing only the immediate effects of a short-term price change may be irrelevant. Similarly, if an experiment – possibly unintentionally – targets only a specific group of customers or takes place at a time that is unusual and unrepresentative of ‘normal’ conditions, it might not be reliable to generalize the results. Particularly in companies that use A/B tests a lot, it may be necessary to check that the customer groups are not affected by previous testing. Finally, although the test should be relevant, of course, it presumably should not involve testing conduct that could be illegal, such as examining whether certain communication leads to price-fixing.

Secondly, the process for conducting the experiment should enhance and demonstrate its rigor and ‘honesty’, in that the company conducting the analysis should know what it is looking to test and establish in advance what different results would imply. Ideally, this should be done in consultation with a competition authority. Obviously, such pre-registration of objectives carries the risk that the result will not support the argument the parties hoped for, but this very risk itself increases the credibility of the experiment itself (and a reason why pre-registration is standard practice in clinical trials). Just as when they are presented with surveys, competition authorities are naturally suspicious that they will only be shown results that are favorable. Competition Authorities generally prefer to be consulted on surveys and the same is likely to apply to experiments. Indeed, many of the procedural aspects of the CMA ‘Good Practice’ Guidelines on surveys seem very relevant to using and presenting experimental evidence to competition authorities.[6]

Like any source of evidence, the results of experiments need to be considered together with other evidence, such as observed behavior. Ideally, the results should be consistent with such other evidence – in the Spotify example above, the results aligned well with econometric analysis of historical data by some experts at Compass Lexecon assessing how changes in Apple’s Rules and in Spotify’s use of Apple’s In-App Payment system affected subscriptions by iOS users.

For their part, competition authorities should become more expert in critically evaluating such experiments. They might also consider asking parties to run such experiments, just as they often ask for surveys, although there may be legal constraints on whether a state body can require companies to change prices or other terms ‘for real’ for the purposes of their research. If such procedural hurdles can be overcome, such techniques could become common, especially in the increasing share of cases that are for digital products. Perhaps, too, experiments can help to improve the (sometimes woeful) performance of behavioral remedies, removing some of the speculation about how a change of price, brand, or availability might perform in the market.

[1] The views expressed in this article are the views of the authors only and do not necessarily represent the views of Compass Lexecon, its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, its employees, or its clients. This article is informed by advice provided to Spotify in the context of the European Commission’s investigation into Apple on App Store rules for music streaming providers.

[2] Press release: The Prize in Economic Sciences 2019. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2021. Accessed Friday 15 October 2021: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2019/press-release/

[3] A famous example is Google testing which of 41 shades of the color blue to use on their website. https://stopdesign.com/archive/2009/03/20/goodbye-google.html

[4] The Commission sent Apple a Statement of Objections on 30 April 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_21_2093

[5] In September 2021, it was announced that the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) was closing its investigation of Apple, after Apple offered a global commitment to permit ‘reader’ applications such as Spotify to use in-app links to a sign-up web page. Experts from Compass Lexecon assisted Spotify in its submissions to the JFTC.

[6] See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/mergers-consumer-survey-evidence-design-and-presentation/good-practice-in-the-design-and-presentation-of-customer-survey-evidence-in-merger-cases.